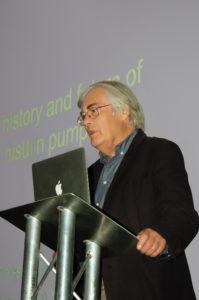

Professor John Pickup has been involved in diabetes care for most of his career in medicine. He’s been there from the beginning, when continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSii for short) was in its inception. I talked to him recently as he looked back in time to assess how things have changed, then turned his experienced eye to the future and tells of what he sees there. By Sue Marshall

The 1970s are remembered for flares, flower power and fabulous hair-dos, this decade also saw the start of modern-day computing with microprocessors making their debut and personal computers being coined. Fibre optics started to be ‘a thing’, along with commercially available VCRs and video games and someone at Sony thought we should be walking around with music in our pockets and sold us the Walkman.

But, lest we forget, it was in this decade – from 1978 – that we had the introduction of what is now called SMBG – self monitoring of blood glucose, or as most of us call ‘em, blood tests. And that was just before the dawn of the insulin pen in 1981.

Already in 1974 Slama, et al, had conducted an experiment in Paris whereby several patients carried a pump around on their shoulders for up to five days while it infused insulin intravenously. This method did produce good glycaemic control, but it was intravenously, which was not ideal on several fronts, and could only be undertaken on a short-term basis.

Shortly after this, at Guy’s Hospital in London, the concept of an improved means of delivering insulin to people with diabetes in order to improve control came into being. It was in the form of a wearable insulin pump and the concept was called CSII, or Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion, the brainchild of Professor Harry Keen. Subcutaneous infusion was a far better idea, if they could figure out how to do it. The time was 1976.

Shortly after this, at Guy’s Hospital in London, the concept of an improved means of delivering insulin to people with diabetes in order to improve control came into being. It was in the form of a wearable insulin pump and the concept was called CSII, or Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion, the brainchild of Professor Harry Keen. Subcutaneous infusion was a far better idea, if they could figure out how to do it. The time was 1976.

Emeritus Professor of Diabetes and Metabolism John Pickup has been a part of diabetes care at Kings College London School of Medicine for most of his career, and also Guys Hospital London for many years. Now semi-retired, he says, “My little secret is that I hate much of modern technology, everything from tweeting and Facebook to ‘unexpected item in bagging area’. It seems rather amazing to me that we are only just coming up to 100 years of injecting insulin.”

He’s not wrong; Doctor F.G. Banting and his assistant C.H. Best discovered insulin during experiments conducted in Canada in 1920. It took a while before insulin had been safely extracted and used to treat patients with Type 1 diabetes, ever since saving the lives of millions. However it wasn’t until the mid-‘60s to ‘80s that there were more significant breakthroughs in the treatment of T1D with home-blood testing, insulin pens, and pumps coming along. But where die they come along from?

Portable option

Portable option

Pickup was part of the world’s first trail of a portable insulin pump. He looks back, “It was already becoming apparent that good control was directly related to a reduction in the development of diabetes complications, before we even had the results of the DCCT* trial that proved this as a fact. Prior to that we did not know for certain that sustained high blood sugars, or overall extreme glucose variation was what was actually causing the damage.”

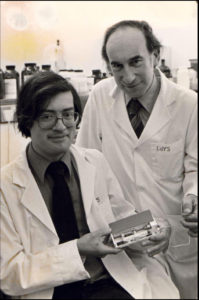

In 1974 Pickup had met Dr John Parsons, a pharmacologist at the National Institute for Medical Research in Mill Hill, London. He had a basic drugs infuser – called the Mill Hill Infuser – which was at that time used for infusing parathyroid hormone into animals. They actually met in Boston, Massachusetts, Pickup at that point being in the Massachusetts General Hospital Endocrine Unit while Parsons was a senior medical researcher on leave from Mill Hill at the Mass General, which was a well-known centre of calcium metabolism at the time, Parsons being interested in parathyroid hormone action. “I think we bonded because he knew my PhD supervisor at Oxford, and it was he who recommend I meet up with Parsons when later I went to Boston as a clinical medical student,” recalls Pickup. “ I then wondered if the Mill Hill Infuser could be used for delivering insulin, and in that way mimic the control of someone who did not have diabetes,” he says, “We knew it would need to include patient-activated boosts (or boluses) at mealtimes.”

An infuser – or pump — was then made for human use, a pump which now resides in the Science Museum in London. “From this point on,” says Pickup, “dramatic improvement in diabetes control was probably possible.” Pickup then worked on this with Harry Keen, a Professor of Human Metabolism at Guy’s Hospital and Medical School.

Shortly after, Pickup and Keen presented this concept to the EASD meeting in Geneva in 1977. Pickup recalls, “Feedback was generally very positive and people were intrigued, though there were many reservations and doubts about whether the technique had any future in diabetes care. There was a worry that continuous infusion would lead to much hypoglycaemia and that patients would not like or tolerate wearing a machine like this. All turned out not true in reality. It’s interesting to note the early correlation that insulin pump users were among the very first people to take up home blood testing too, gaining the greater control that lead to far fewer hypos. People with diabetes who understood about the benefits of improved control did not worry overly about either wearing a pump or pricking their fingers.”

Shortly after, Pickup and Keen presented this concept to the EASD meeting in Geneva in 1977. Pickup recalls, “Feedback was generally very positive and people were intrigued, though there were many reservations and doubts about whether the technique had any future in diabetes care. There was a worry that continuous infusion would lead to much hypoglycaemia and that patients would not like or tolerate wearing a machine like this. All turned out not true in reality. It’s interesting to note the early correlation that insulin pump users were among the very first people to take up home blood testing too, gaining the greater control that lead to far fewer hypos. People with diabetes who understood about the benefits of improved control did not worry overly about either wearing a pump or pricking their fingers.”

The first full research paper on CSII by J Pickup et all was published in the BMJ in 1978.

A company based in south Norwood called Muirhead Ltd, which manufactured new-fangled fax machines, made the early pumps. In 1983 they had made the first microprocessor-controlled insulin pump, later licensed to Novo Nordisk. The first insulin used in pumps was pork Actrapid, but by the late 1980s genetic engineering of human insulin using bacteria had been done, leading to the first time any human had been given a synthesised protein. Guys Hospital helped to test the safety and efficacy of this innovation in medial care. Pickup recalls, “Everyone was terrified of what might happen.” And the brave souls who tested it? Step up candidate number one, Professor Harry Keen. And candidate number two? Dr John Pickup.

It was around this time, 1983, that the team at Guys started to research glucose sensors, part of the direction of travel to today’s CGM options, which are now becoming much more widely used and accepted, though more than 30 years later.

Are we there yet?

Are we there yet?

We’ve come a long way, people, but it’s been slow progress. Bearing in mind the fact that this technology has been around a while, how come we have seen what is arguably a very low uptake of it? Pickup says that there is, “clear effectiveness of the use of this technology, but availability is highly variable. New technology can be more expensive than existing technology, and undoubtedly there is also still some resistance to it both from patients and HCPs. However, what has been proven with insulin pump use is that severe hypos are reduced, by up to 75%, with an almost immediate 0.6% improvement in HbA1c after switching from multiple daily injections.”

Speaking with Pickup, it’s easy to see that he’s just as frustrated as anyone else at the slow progress in terms of uptake and availability, with wearable diabetes technology still being used by relatively few diabetics, despite the numbers who could almost certainly benefit from it. Pickup recalls, “In 1972 there was a 50th anniversary meeting about the first use of insulin. Doctor Stuart Soeldner put up an image of his vision of an implantable artificial pancreas. He presented it as a concept saying that he though he would have a viable model five years from then. We are now nearly 50 years on from that point and artificial insulin pumps are only now starting to look like a true reality.”

Clearly these treatments need brave volunteers to try them out. Then, over time, they need proof of numbers in terms of proving improved control, as well as proof of concept (that they work at all, that people will wear them and can learn how to use them). Long-term safety and efficacy needs to be established, and that takes time and is costly for the companies doing the research and development. The good news is that there are more insulin pumps out there than ever before, in terms of both the number of people using them and the numbers of insulin pumps now available. Says Pickup, “It’s people with least good control that get put into pumps. They tend to be prone to having hypos or have very unpredictable control. Clearly they need help, but a Swedish study showed that anyone with Type 1 diabetes will live longer if they can gain good control with the use of CSII, so there’s a provable reduction in mortality too.”

Looking ahead

In all, bearing in mind that ‘making slow progress’ is a common enough phrase, Pickup feels that, “Overall we have made great progress over the last 40 years or so, with the likelihood of many exciting advances coming in the near future. We do not yet know much improved care might come from many years of use of CSII and CGM, for example, and that may prove very persuasive used in combination. Also, improved ‘quality of life’ is starting to be really appreciated by the medical community, consideration being given to the greater wellbeing of those who use infusion as a method of insulin delivery. People on pumps seem to be more productive, which is to say that they can hold down their jobs without being too troubled by their diabetes on a day-to-day basis.”

Pickup is aware that part of the problem with pump uptake and availability is due to a hesitancy on the part of some healthcare professionals, that some see it as too much trouble, not just educating patients on how to use a pump, but having to justify giving one to their patients. “I think that there has been some unhelpful misinformation over the years too,” says Pickup. “I do think it’s a terrible shame that pumps are not offered to patients, that they have to ask for it, in some cases they have to fight pretty hard to get access. There is a recognised resistance towards technology in the UK, a generalised problem with the uptake of many new treatments, including healthcare technology, and not just in diabetes care. In general people in the UK are fast adaptors and have a high uptake of new technology like computers and smart phones compared to some other developed countries, but UK healthcare is paradoxically slow to take up new medicines and fully implement recognised valuable procedures like hip and cataract operations.”

Should existing pump users shout louder about their experience? “The voice of the patient is really being listened to now,” says Pickup. “Social media has its moments, but it’s hard to control, and you often see bad experiences alongside the good ones making for an unclear picture. It soften seems to be about who can shout the loudest. I recall that at the last NICE review in 2008 patient representatives were included as well as HCPs. There was feedback and advice from charities like JDRF, INPUT and others. Patient’s stories about how technologies have improved their lives were very impressive. I expect that will increasingly be the case as regards future technologies. Organsations like INPUT and Desang Diabetes Magazine help to marshall that impetus for the good.”

News items and features like this appear in the Desang Diabetes Magazine, our free-to-receive digital journal (see below). We cover diabetes news, diabetes management equipment (diabetes ‘kit’ such as insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitoring equipment) and news about food suitable for a diabetic diet including a regular Making Carbs Count column. We just need your email address to subscribe you (it’s free, and you can easily unsubscribe should you wish to).